Predicting time to death after withdrawal in controlled donation after circulatory death (DCD) donors : A comparison of 100 DCD lung transplant (LTx) donors versus 59 potential DCD donors that did not progress

Bronwyn Levvey1, Shuji Okahara2, Mark McDonald3, Rohit D'Costa4, Helen Opdam4, David Pilcher2, Gregory Snell1.

1Lung Transplant Service, The Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Australia; 2Australian & New Zealand Intensive Care Research Centre, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia; 3Analytics and Technology, Organ and Tissue Authority, Canberra, Australia; 4DonateLife Victoria, DonateLife Agency, Melbourne, Australia

Introduction: Since 2006, controlled DCD donors have been routinely utilized for LTx by our institution, now contributing an additional 25-30 % LTx annually. Donation of lungs from a potential DCD donor can only occur if the patient dies ≤90 minutes post withdrawal of cardio-respiratory support (WCRS). However, 20-25% of potential DCD donors still do not progress to asystole in 90 minutes, leading to disappointment for the patient’s grieving family as well as having major resourcing implications for the donation and transplant teams. Prediction of which patients will die within the 90 minutes limit remains problematic. Previous studies have evaluated ICU variables and clinical WCRS practices to try and predict time to death with limited success. In this study, we compared a cohort of LTx DCD donors with a cohort of potential DCD donors who did not progress, looking for factors that may better predict time to death.

Methods: This retrospective study reviewed donor records of all potential DCD donors that were referred to our institution from our local state donor agency, between 2014 and 2018. We included data from all potential DCD donors that been formally accepted as suitable for LTx and where our LTx surgical retrieval team actually attended the donor hospital. Variables evaluated included donor demographics and medical history, hospital location, cause of injury leading to WCRS, ICU hemodynamic and ventilation data, Apache II Score, time, location and method of WCRS and time to death. Analysis of comparison between the 2 cohorts was done using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests and chi-square tests.

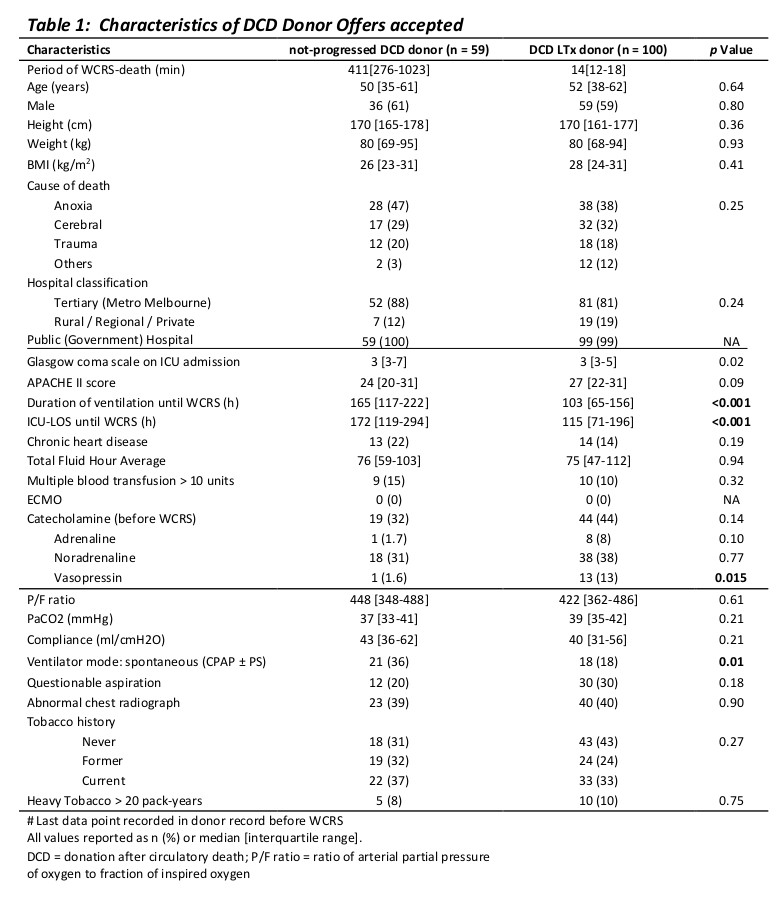

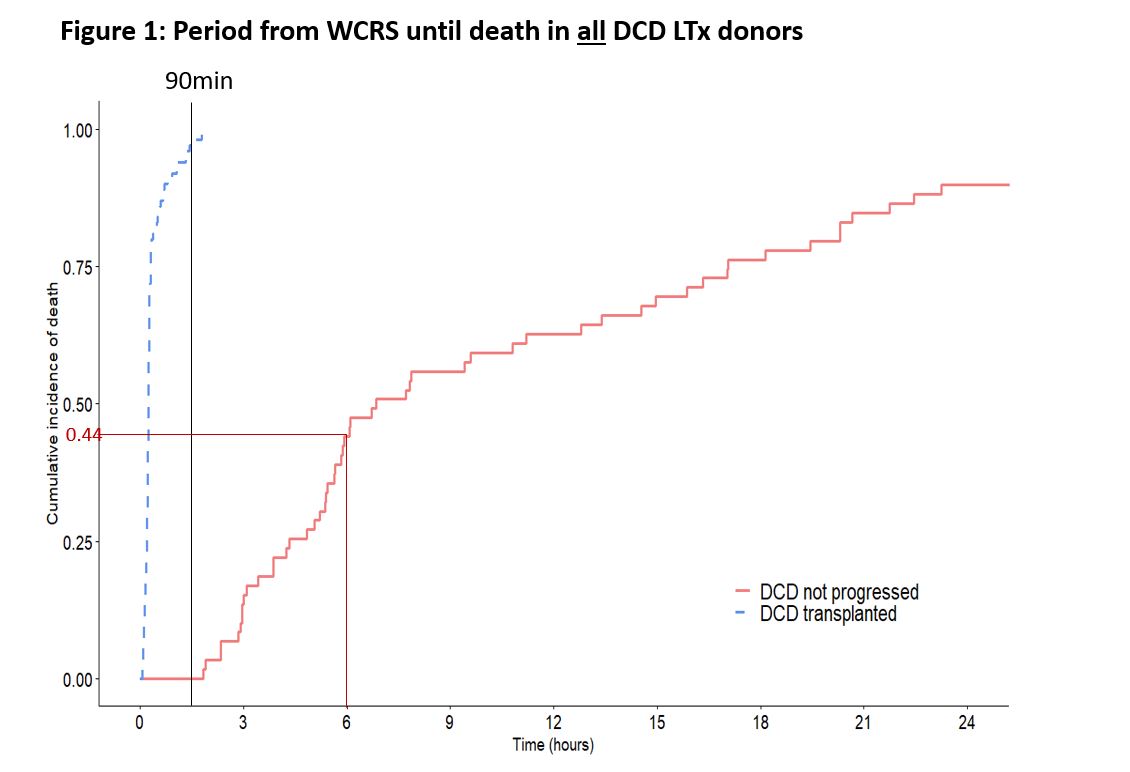

Results: Between 2014-2018, there were 334 DCD donor referrals to our program, resulting in 159 (48%) potential DCD donors attended for potential LTx retrieval. 100/159 (63%) progressed to DCD LTx, but 59 donors (37%) did not progress in required 90 minutes. Potential DCD donors that did not progress were less likely to be on vasopressin compared to DCD LTx donors (p<0.02), they were more likely to be in CPAP ventilator mode (p<0.01) and in ICU and ventilated longer (P<0.001) before WCRS. There were no differences in donor demographics, P/F ratio, cause of injury leading to WCRS, hospital type/location, donor hemodynamics, abnormal CXR or smoking history (Table 1). Of the 59 who did not die within 90 minutes of WCRS, 26 patients (44%) died within the subsequent 6 hours (Figure 1).

Conclusions: Progression to asystole within 90 minutes and subsequent lung donation for DCD LTx is more likely where the potential lung donor has a requirement for mandatory-mode mechanical ventilatory support and vasopressin, suggesting they have a significant brainstem neurological injury. Additionally, development of a protocol that allows potential retrieval of donor lungs in the subsequent 6hrs after WCRS would significantly increase the yield of lungs from this pool of otherwise acceptable donors.