Travel for transplantation: Impact on liver transplant candidates and recipients in the United States

Hillary Braun1, Dominic Amara2, Amy M. Shui4, Peter G. Stock1, Ryutaro Hirose1, Francis L. Delmonico3, Nancy L. Ascher1.

1Department of Surgery, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, United States; 2School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, United States; 3Department of Surgery, Massachussetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States; 4Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, United States

Introduction: Travel for transplantation is justifiable in certain circumstances, but the fundamental concept of travel for transplantation threatens attempts at self-sufficiency and can devolve into transplant tourism if not highly regulated. In the United States (US), there are four populations who compete for liver transplantation (LT): 1) singly listed (SL) citizens, 2) multiply listed citizens (ML), 3) non-citizen, non-residents (NCNR), and 4) non-citizen residents (NC-R). ML, NCNR, and NC-R engage in some amount of travel for transplantation. The purpose of this investigation was to describe these groups and to compare their outcomes on the waitlist (WL) and after LT.

Materials and Methods: Using United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) data, all liver WL candidates from January 1, 2003-December 31, 2017 were reviewed. Re-transplant candidates, pediatric patients, and patients listed for multiple organs were excluded. SL were defined as those with a single listing. ML were defined as patients with overlapping listing dates prior to their initial transplant or WL removal date. NCNR patients and NC-R patients were identified by citizenship status. Descriptive statistics were calculated. WL outcomes were analyzed using competing risks analysis. Post-transplant graft and patient survival were compared using Kaplan Meier.

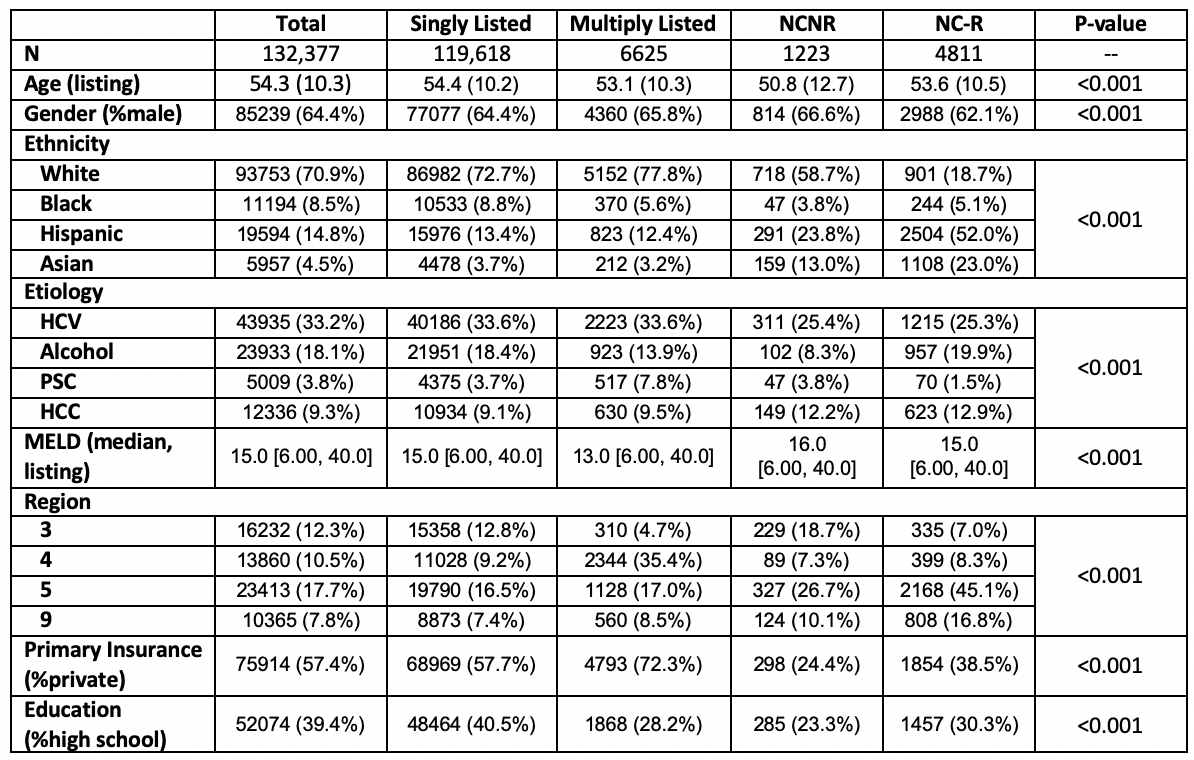

Results: 132,277 WL registrants resulting in 75,955 LT were included. There were significant differences in nearly all of the demographic variables (Table). ML patients were predominantly white, privately insured, highly educated, and were transplanted at a significantly lower match MELD. NCNR patients were significantly younger, had a greater proportion of males, and spent the shortest time on the WL. NC-R patients were 75% Asian or Hispanic and had the greatest proportion of public insurance (58.5%). NCNR patients received the most live donor grafts (8.3%, p<0.001), while ML patients received the greatest proportion of DCD grafts (6.2%, p<0.001).

In competing risks analysis (n=131,569) controlling for MELD and hepatocellular carcinoma, ML patients had a 24% increase in the rate of transplant and NCNR patients had a 10% increase in the rate of transplant compared with SL patients (p-values <0.001 and 0.02, respectively).

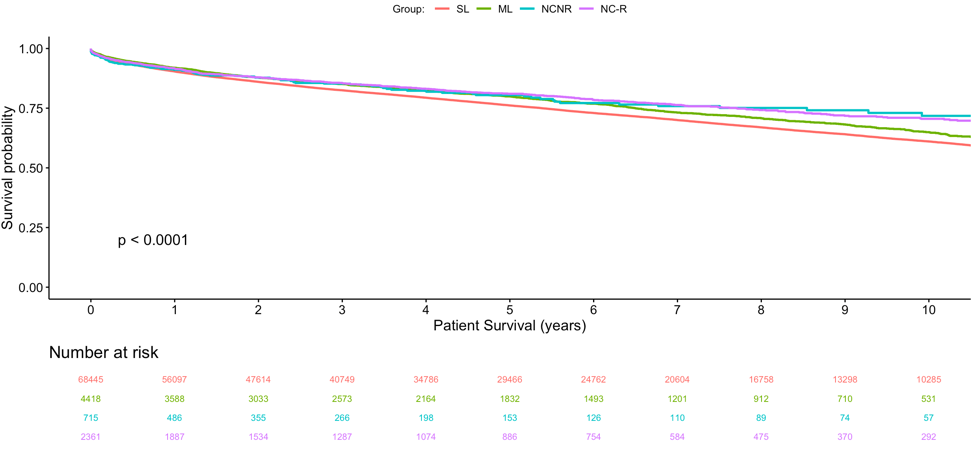

In survival analysis of LT recipients (n=75,955), there were significant differences in both overall graft (p<0.001) and patient (p<0.001, Figure 2) survival among the four groups. SL patients had the worst overall graft and patient survival, while NC-R and NCNR patients had the best outcomes.

Discussion: Transplant tourism begins with patients who are willing to travel for transplant. Our analysis indicates that patients who travel (ML and NCNR) have increased transplant rates and better long-term survival when compared with SL patients.

Conclusion: SL patients in the US constitute 90% of the LT WL and recipient list, yet they have lower transplant rates and the worst overall survival.

AS is part of the Biostatistics Core that is generously supported by the UCSF Department of Surgery..